Fibred category

Fibred categories are abstract entities in mathematics used to provide a general framework for descent theory. They formalise the various situations in geometry and algebra in which inverse images (or pull-backs) of objects such as vector bundles can be defined. As an example, for each topological space there is the category of vector bundles on the space, and for every continuous map from a topological space X to another topological space Y is associated the pullback functor taking bundles on Y to bundles on X. Fibred categories formalise the system consisting of these categories and inverse image functors. Similar set-ups appear in various guises in mathematics, in particular in algebraic geometry, which is the context in which fibred categories originally appeared. Fibrations also play an important role in categorical type theory and theoretical computer science, particularly in models of dependent type theory.

Fibred categories were introduced by Alexander Grothendieck in Grothendieck (1959), and developed in more detail by himself and Jean Giraud in Grothendieck (1971) in 1960/61, Giraud (1964) and Giraud (1971).

Contents |

Background and motivations

There are many examples in topology and geometry where some types of objects are considered to exist on or above or over some underlying base space. The classical examples include vector bundles, principal bundles and sheaves over topological spaces. Another example is given by "families" of algebraic varieties parametrised by another variety. Typical to these situations is that to a suitable type of a map f: X → Y between base spaces, there is a corresponding inverse image (also called pull-back) operation f* taking the considered objects defined on Y to the same type of objects on X. This is indeed the case in the examples above: for example, the inverse image of a vector bundle E on Y is a vector bundle f*(E) on X.

Moreover, it is often the case that the considered "objects on a base space" form a category, or in other words have maps (morphisms) between them. In such cases the inverse image operation is often compatible with composition of these maps between objects, or in more technical terms is a functor. Again, this is the case in examples listed above.

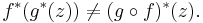

However, it is often the case that if g: Y → Z is another map, the inverse image functors are not strictly compatible with composed maps: if z is an object over Z (a vector bundle, say), it may well be that

Instead, these inverse images are only naturally isomorphic. This introduction of some "slack" in the system of inverse images causes some delicate issues to appear, and it is this set-up that fibred categories formalise.

The main application of fibred categories is in descent theory, concerned with a vast generalisation of "glueing" techniques used in topology. In order to support descent theory of sufficient generality to be applied in non-trivial situations in algebraic geometry the definition of fibred categories is quite general and abstract. However, the underlying intuition is quite straightforward when keeping in mind the basic examples discussed above.

Formal definitions

There are two essentially equivalent technical definitions of fibred categories, both of which will be described below. All discussion in this section ignores the set-theoretical issues related to "large" categories. The discussion can be made completely rigorous by, for example, restricting attention to small categories or by using universes.

Cartesian morphisms and functors

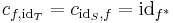

If φ: F → E is a functor between two categories and S is an object of E, then the subcategory of F consisting of those objects x for which φ(x)=S and those morphisms m satisfying φ(m)=idS, is called the fibre category (or fibre) over S, and is denoted FS. The morphisms of FS are called S-morphisms, and for x,y objects of FS, the set of S-morphisms is denoted by HomS(x,y). The image by φ of an object or a morphism in F is called its projection (by φ). If f is a morphism of E, then those morphisms of F that project to f are called f-morphisms, and the set of f-morphisms between objects x and y in F is denoted by Homf(x,y). A functor φ: F → E is also called an E-category, or said to make F into an E-category or a category over E. An E-functor from an E-category φ: F → E to an E-category ψ: G → E is a functor α: F → G such that ψ o α = φ. E-categories form in a natural manner a 2-category, with 1-morphisms being E-functors, and 2-morphisms being natural transformations between E-functors whose components lie in some fibre.

A morphism m: x → y in F is called E-cartesian (or simply cartesian) if it satisfies the following condition:

- if f: T → S is the projection of m, and if n: z → y is an f-morphism, then there is precisely one T-morphism a: z → x such that n = m o a.

A cartesian morphism m: x → y is called an inverse image of its projection f = φ(m); the object x is called an inverse image of y by f.

The cartesian morphisms of a fibre category FS are precisely the isomorphisms of FS. There can in general be more than one cartesian morphism projecting to a given morphism f: T → S, possibly having different sources; thus there can be more than one inverse image of a given object y in FS by f. However, it is a direct consequence of the definition that two such inverse images are isomorphic in FT.

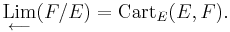

An E-functor between two E-categories is called a cartesian functor if it takes cartesian morphisms to cartesian morphisms. Cartesian functors between two E-categories F,G form a category CartE(F,G), with natural transformations as morphisms. A special case is provided by considering E as an E-category via the identity functor: then a cartesian functor from E to an E-category F is called a cartesian section. Thus a cartesian section consists of a choice of one object xS in FS for each object S in E, and for each morphism f: T → S a choice of an inverse image mf: xT → xS. A cartesian section is thus a (strictly) compatible system of inverse images over objects of E. The category of cartesian sections of F is denoted by

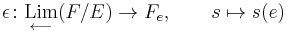

In the important case where E has a terminal object e (thus in particular when E is a topos or the category E/S of arrows with target S in E) the functor

is fully faithful (Lemma 5.7 of Giraud (1964)).

Fibred categories and cleaved categories

The technically most flexible and economical definition of fibred categories is based on the concept of cartesian morphisms. It is equivalent to a definition in terms of cleavages, the latter definition being actually the original one presented in Grothendieck (1959); the definition in terms of cartesian morphisms was introduced in Grothendieck (1974) in 1960–1961.

An E category φ: F → E is a fibred category (or a fibred E-category, or a category fibred over E) if each morphism f of E whose codomain is in the range of projection has at least one inverse image, and moreover the composition m o n of any two cartesian morphisms m,n in F is always cartesian. In other words, an E-category is a fibred category if inverse images always exist (for morphisms whose codomains are in the range of projection) and are transitive.

If E has a terminal object e and if F is fibred over E, then the functor ε from cartesian sections to Fe defined at the end of the previous section is an equivalence of categories and moreover surjective on objects.

If F is a fibred E-category, it is always possible, for each morphism f: T → S in E and each object y in FS, to choose (by using the axiom of choice) precisely one inverse image m: x → y. The class of morphisms thus selected is called a cleavage and the selected morphisms are called the transport morphisms (of the cleavage). A fibred category together with a cleavage is called a cleaved category. A cleavage is called normalised if the transport morphisms include all identities in F; this means that the inverse images of identity morphisms are chosen to be identity morphisms. Evidently if a cleavage exists, it can be chosen to be normalised; we shall consider only normalised cleavages below.

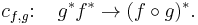

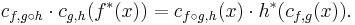

The choice of a (normalised) cleavage for a fibred E-category F specifies, for each morphism f: T → S in E, a functor f*: FS → FT: on objects f* is simply the inverse image by the corresponding transport morphism, and on morphisms it is defined in a natural manner by the defining universal property of cartesian morphisms. The operation which associates to an object S of E the fibre category FS and to a morphism f the inverse image functor f* is almost a contravariant functor from E to the category of categories. However, in general it fails to commute strictly with composition of morphisms. Instead, if f: T → S and g: U → T are morphisms in E, then there is an isomorphism of functors

These isomorphisms satisfy the following two compatibilities:

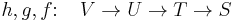

- for three consecutive morphisms

and object

and object  the following holds:

the following holds:

It can be shown (see Grothendieck (1971) section 8) that, inversely, any collection of functors f*: FS → FT together with isomorphisms cf,g satisfying the compatibilities above, defines a cleaved category. These collections of inverse image functors provide a more intuitive view on fibred categories; and indeed, it was in terms of such compatible inverse image functors that fibred categories were introduced in Grothendieck (1959).

The paper by Gray referred to below makes analogies between these ideas and the notion of fibration of spaces.

These ideas simplify in the case of groupoids, as shown in the paper of Brown referred to below, which obtains a useful family of exact sequences from a fibration of groupoids.

Splittings and split fibred categories

A (normalised) cleavage such that the composition of two transport morphisms is always a transport morphisms is called a splitting, and a fibred category with a splitting is called a split (fibred) category. In terms of inverse image functors the condition of being a splitting means that the composition of inverse image functors corresponding to composable morphisms f,g in E equals the inverse image functor corresponding to f o g. In other words, the compatibility isomorphisms cf,g of the previous section are all identities for a split category. Thus split E-categories correspond exactly to true functors from E to the category of categories.

Unlike cleavages, not all fibred categories admit splittings. For an example, see below.

Co-cartesian morphisms and co-fibred categories

One can invert the direction of arrows in the definitions above to arrive at corresponding concepts of co-cartesian morphisms, co-fibred categories and split co-fibred categories (or co-split categories). More precisely, if φ: F →E is a functor, then a morphism m: x → y in F is called co-cartesian if it is cartesian for the opposite functor φop: Fop → Eop. Then m is also called a direct image and y a direct image of x for f = φ(m). A co-fibred E-category is anE-category such that direct image exists for each morphism in E and that the composition of direct images is a direct image. A co-cleavage and a co-splitting are defined similarly, corresponding to direct image functors instead of inverse image functors.

Properties

The 2-categories of fibred categories and split categories

The categories fibred over a fixed category E form a 2-category Fib(E), where the category of morphisms between two fibred categories F and G is defined to be the category CartE(F,G) of cartesian functors from F to G.

Similarly the split categories over E form a 2-category Scin(E) (from French catégorie scindée), where the category of morphisms between two split categories F and G is the full sub-category ScinE(F,G) of E-functors from F to G consisting of those functors that transform each transport morphism of F into a transport morphism of G. Each such morphism of split E-categories is also a morphism of E-fibred categories, i.e., ScinE(F,G) ⊂ CartE(F,G).

There is a natural forgetful 2-functor i: Scin(E) → Fib(E) that simply forgets the splitting.

Existence of equivalent split categories

While not all fibred categories admit a splitting, each fibred category is in fact equivalent to a split category. Indeed, there are two canonical ways to construct an equivalent split category for a given fibred category F over E. More precisely, the forgetful 2-functor i: Scin(E) → Fib(E) admits a right 2-adjoint S and a left 2-adjoint L (Theorems 2.4.2 and 2.4.4 of Giraud 1971), and S(F) and L(F) are the two associated split categories. The adjunction functors S(F) → F and F → L(F) are both cartesian and equivalences (ibid.). However, while their composition S(F) → L(F) is an equivalence (of categories, and indeed of fibred categories), it is not in general a morphism of split categories. Thus the two constructions differ in general. The two preceding constructions of split categories are used in a critical way in the construction of the stack associated to a fibred category (and in particular stack associated to a pre-stack).

Examples

- Categories of arrows: For any category E the category of arrows A(E) in E has as objects the morphisms in E, and as morphisms the commutative squares in E (more precisely, a morphism from (f: X → T) to (g: Y → S) consists of morphisms (a: X → Y) and (b: T → S) such that bf = ga). The functor which takes an arrow to its target makes A(E) into an E-category; for an object S of E the fibre ES is the category E/S of S-objects in E, i.e., arrows in E with target S. Cartesian morphisms in A(E) are precisely the cartesian squares in E, and thus A(E) is fibred over E precisely when fibre products exist in E.

- Fibre bundles: Fibre products exist in the category Top of topological spaces and thus by the previous example A(Top) is fibred over Top. If Fib is the full subcategory of A(Top) consisting of arrows that are projection maps of fibre bundles, then FibS is the category of fibre bundles on S and Fib is fibred over Top. A a choice of a cleavage amounts to a choice of ordinary inverse image (or pull-back) functors for fibre bundles.

- Vector bundles: In a manner similar to the previous examples the projections (p: V → S) of real (complex) vector bundles to their base spaces form a category VectR (VectC) over Top (morphisms of vector bundles respecting the vector space structure of the fibres). This Top-category is also fibred, and the inverse image functors (are the ordinary pull-back functors for vector bundles. These fibred categories are (non-full) subcategories of Fib.

- Sheaves on topological spaces: The inverse image functors of sheaves make the categories Sh(S) of sheaves on topological spaces S into a (cleaved) fibred category Sh over Top. This fibred category can be described as the full sub-category of A(Top) consisting of etale spaces of sheaves. As with vector bundles, the sheaves of groups and rings also form fibred categories of Top.

- Sheaves on topoi: If E is a topos and S is an object in E, the category ES of S-objects is also a topos, interpreted as the category of sheaves on S. If f: T → S is a morphism in E, the inverse image functor f* can be described as follows: for a sheaf F on ES and an object p: U → T in ET one has f*F(U) = HomT(U, f*F) equals HomS(f o p, F) = F(U). These inverse image make the categories ES into a split fibred category on E. This can be applied in particular to the "large" topos TOP of topological spaces.

- Quasi-coherent sheaves on schemes: Quasi-coherent sheaves form a fibred category over the category of schemes. This is one of the motivating examples for the definition of fibred categories.

- Fibred category admitting no splitting: A group G can be considered as a category with one object and the elements of G as the morphisms, composition of morphisms being given by the group law. A group homomorphism f: G → H can then be considered as a functor, which makes G into a H-category. It can be checked that in this set-up all morphisms in G are cartesian; hence G is fibred over H precisely when f is surjective. A splitting in this setup is a (set-theoretic) section of f which commutes strictly with composition, or in other words a section of f which is also a homomorphism. But as is well-known in group theory, this is not always possible (one can take the projection in a non-split group extension).

- Co-fibred category of sheaves: The direct image functor of sheaves makes the categories of sheaves on topological spaces into a co-fibred category. The transitivity of the direct image shows that this is even naturally co-split.

See also

References

- Giraud, Jean (1964). "Méthode de la descente". Mémoires de la Société Mathématique de France 2: viii+150.

- Giraud, Jean (1971). Cohomologie non abélienne. Springer. ISBN 3-540-05307-7

- Grothendieck, Alexander (1959). "Technique de descente et théorèmes d'existence en géométrie algébrique. I. Généralités. Descente par morphismes fidèlement plats". Séminaire Bourbaki 5 (Exposé 190): viii+150.

- Gray, John W. (1966). "Fibred and cofibred categories". Proc. Conf. Categorical Algebra (La Jolla, Calif., 1965). Springer Verlag. pp. 21–83.

- Brown, R., "Fibrations of groupoids", J. Algebra 15 (1970) 103-132.

- Grothendieck, Alexander (1971). "Catégories fibrées et descente". Revêtements étales et groupe fondamental. Springer Verlag. pp. 145–194.

- Jacobs, Bart (1999). Categorical Logic and Type Theory. Studies in Logic and the Foundations of Mathematics 141. North Holland, Elsevier. ISBN 0-444-50170-3. http://www.cs.ru.nl/B.Jacobs/CLT/bookinfo.html.

- Angelo Vistoli, Notes on Grothendieck topologies, fibered categories and descent theory, arXiv:math.AG/0412512.

- Fibred Categories à la Bénabou, Thomas Streicher

- An introduction to fibrations, topos theory, the effective topos and modest sets, Wesley Phoa